Collection: Ludvig Karsten

-

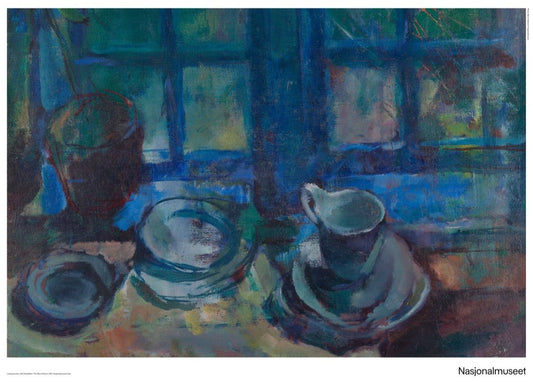

The blue kitchen

Vendor:Ludvig KarstenRegular price From 150,00 NOKRegular priceUnit price per -

The red kitchen

Vendor:Ludvig KarstenRegular price From 150,00 NOKRegular priceUnit price per -

Spring, Skagen

Vendor:Ludvig KarstenRegular price From 150,00 NOKRegular priceUnit price per -

In front of the mirror

Vendor:Ludvig KarstenRegular price From 150,00 NOKRegular priceUnit price per -

In the brewhouse

Vendor:Ludvig KarstenRegular price From 150,00 NOKRegular priceUnit price per -

The man with the silver mug

Vendor:Ludvig KarstenRegular price From 150,00 NOKRegular priceUnit price per