Collection: Édouard Manet

-

Mme Manet in the conservatory

Vendor:Édouard ManetRegular price From 150,00 NOKRegular priceUnit price per -

From the World Exhibition in Paris in 1867

Vendor:Édouard ManetRegular price From 150,00 NOKRegular priceUnit price per -

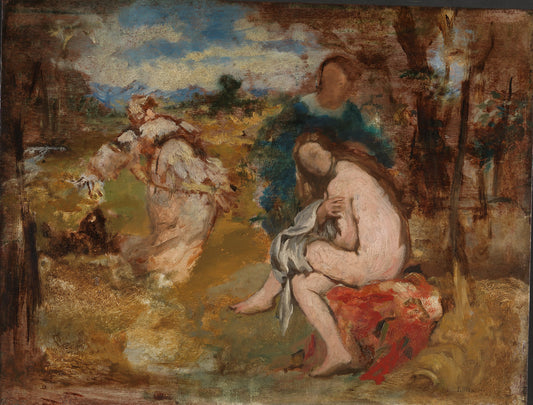

Moses exists

Vendor:Édouard ManetRegular price From 150,00 NOKRegular priceUnit price per